Author: Richard Warren

‘The “short story” was the crystallisation of what I had to keep out of my consciousness while painting. […] That is how I began to write in earnest. A lot of discarded matter collected there, as I was painting or drawing, in the back of my mind – in the back of my consciousness. […] It imposed itself upon me as a complementary creation.’

The context is a recollection of a student painting of an elderly Breton beggar; in order to safeguard the visual quality of the image, Lewis found himself obliged to suppress his personal reactions to the character of the man. We might say that he was obliged to stop verbalising in order to see clearly, that for the sake of the truthfulness of the image it was necessary to suppress preconceptions and the urge to ‘meaning’.

This single mindedness was presented as a drawing technique by Betty Edwards in 1979 in her popular teaching manual Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. Put simply, Edwards located visual awareness in the right brain hemisphere, finding it silent, global and simultaneous, as opposed to the verbal, analytical and sequential thinking of the dominant left brain. To allow the former to operate effectively, the student must learn to suppress the latter. Her schema has not gone entirely uncriticised, but over many years of school art teaching I found it broadly valid; visual art is in the first instance a matter of appearances, and it is important to prevent students from grasping at verbal ideas and intentions that may corrupt those appearances. WL, being ambidextrous, had the wit to gather up and put to use in his writing the verbalisations he had suppressed in the act of image making.

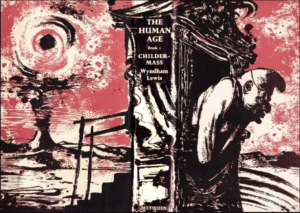

Something close to Edwards’ view is acted out entertainingly in Lewis’ The Childermass (1956), when the appellant Joseph Potter, artist and painter, is examined by the Bailiff:

‘ “I think I notice, Joseph Potter, that even at this solemn moment you are engaged in drawing a sort of mental picture of what is before you. Am I right? Yes? I thought as much. So you are always busy prosecuting your art? When unable to do so on a piece of paper you continue inside your head?” ‘

Potter scratches his head in silence and considers the Bailiff’s face:

‘He catches sight of the large-size-boy’s countenance stylized in a Flemish peasant-grin … Potter’s eye hardens and fixes: … he settles upon the contours of this new object and is soon absorbed in disembowelling it, by planes and tones, and rearranging everything in a logical order.’

His attention is then attracted by a black bystander, whose appearance he proceeds to analyse:

‘Potter … gets down to him on the spot, cutting him up into packets of zones of light and shade, bathing his eyes in the greasy tobacco-black, mustard, Stephens’-ink and sulphur …’

The process of suppression is here in operation. Any ‘literary’ associations for the image of the Bailiff’s face that may float to mind – big boy, Flemish peasant – are shut down as Potter ‘hardens’ and ‘fixes’ his eye; for now, the face is for him merely an accumulation of shapes, but an entirely absorbing one. Throughout the interview, Potter, like his images, remains dumb.

But shouldn’t an artist ‘see’ the interior of his subject? Should s/he not inject into her/his images the lofty significances of the age? We probably expect as much, and the Bailiff certainly does:

‘I’m sure Potter’s not an artist – what? I know an artist when I see one! That was not an artist! We referred to him in that way, oh yes – we do from habit. Artist! That was an imbecile evidently with a mania for measuring and matching, artist doesn’t mean that – rather the opposite I should say. Potter’s talent consists in accepting all things at their face-value, he’s a pure creature of the surface, if you understand me, like the ordinary practitioner of science – they’re very alike those two. The meaning of anything it is almost his creed not to trouble about. […] He saw nothing – in my sense. […] Never to see anything except the outside …’

His crowd of sycophantic appellants agrees, and they give full vent to their prejudices. As Potter passes forward to the City, he must run their gauntlet of derision:

‘Long-hair!’ …‘Pavement-artist!’ … ‘Varnishing-day!’ … ‘Where’s your camera?’

And, perhaps most insulting of all: ‘Cubist!’

All this raises problems. Firstly, images do not stay dumb forever. They proceed to give off apparent meanings, both to us and – even if discovered retrospectively – to the artist him/herself. How this may happen is another discussion.

Secondly, Potter’s observations are fastened on the forms of the world around him; how transferable is his practice to an art that, like that of WL’s Vorticist period, seems non-referential and almost purely abstract, dogmatically anti-real? The principle stands. The artist’s attention is engrossed by the play of formal elements within the work, by-passing any urge to make them carriers of meaning.

Visual art is essentially a matter of appearances. If it were merely a secondary, inefficient way to encode or approximate literary meaning, we would not bother to make it. The voicings of writing, the dumbness of painting and drawing: these are what make them complementary creations.

That may be as inconvenient for us as it is distasteful to the Bailiff.